User:Pangalau/sandbox/British Protectorate of Brunei

State of Brunei Negeri Brunei (Malay) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1888–1942 1942–1945 (Japanese occupation) 1945–1984 | |||||||||

| Anthem: Allah Peliharakan Sultan | |||||||||

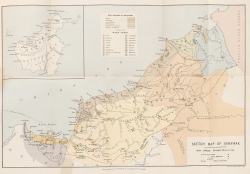

Sarawak and Brunei, 1908 | |||||||||

| Capital | Brunei Town 4°53.417′N 114°56.533′E / 4.890283°N 114.942217°E | ||||||||

| Government | Protectorate | ||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||

• 1888–1906 | Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin | ||||||||

• 1906–1924 | Muhammad Jamalul Alam II | ||||||||

• 1924–1950 | Ahmad Tajuddin | ||||||||

• 1950–1959 | Omar Ali Saifuddien III | ||||||||

| British Resident | |||||||||

• 1906–1907 | Malcolm McArthur[a] | ||||||||

• 1958–1959 | Dennis White[b] | ||||||||

| Legislature | State Council | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Treaty of Protection | 17 September 1888 | ||||||||

• Supplementary Treaty | 2 January 1906 | ||||||||

| 16 December 1941 – 15 June 1945 | |||||||||

| 17 September 1945 | |||||||||

| 29 September 1959 | |||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | BN | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Brunei |

|---|

The term "Brunei Protectorate"[1] or "British Protectorate of Brunei"[2] was used to describe a British Protected State of the United Kingdom that encompassed what is modern-day Brunei from 1888 to 1959. The 1905–1906 Supplementary Treaty created a British Resident, whose counsel was obligatory on behalf of the Sultan in all domains, save Islamic ones. The Resident became the most powerful person in the Sultanate as a result of this system, which essentially gave him substantial administrative authority equivalent to that of a Chief Justice and Menteri Besar combined. The Resident appointed four district officers who answered directly to him, supervising all aspects of administration. He also had the power to appoint traditional authorities like penghulu and ketua kampong.[3]

History

[edit]Treaty of Protection and decline

[edit]Significant changes in Brunei's history occurred as a result of Britain's efforts to increase its influence in the area in the late 19th century in reaction to geopolitical worries about the German Empire and the United States. A significant turning point for Brunei was reached when Sultan Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin and the British government signed the Treaty of Protection with Sir Hugh Low on 17 September 1888, with the intention of obtaining security assurances from Lord Salisbury. Due to this treaty, Brunei's foreign affairs were essentially handed over to Britain, preventing the Sultan from holding direct talks with North Borneo and Sarawak, two nearby states.[4]

However, only two years later, in March 1890, Charles Brooke's annexation of Limbang exposed the treaty's shortcomings and significantly weakened Brunei's sovereignty.[4] Although Brunei was meant to be protected, the Treaty of Protection allowed the British to prioritise their geopolitical interests, resulting in more territorial expansions and internal challenges for Brunei. Sultan Hashim's disappointment with British support peaked in 1902 when he sent a heartfelt letter to King Edward VII, lamenting the lack of assistance his country had received since signing the treaty and the mounting difficulties it faced.[5]

In early 1901, the resurgence of violence in Tutong forced the British Foreign Office to reassess its stance on Brunei.[5] Sultan Hashim's leadership was criticised by many British officials, and sentiment in the region began to shift toward Sarawak's government, which was perceived as offering more equitable taxes and better administration of Brunei's shrinking territory. Concerns raised by Chinese traders about governance further portrayed Brunei as economically fragile and unstable. Despite these challenges, Sultan Hashim remained committed to preserving Brunei's independence, even as financial strains worsened.[6]

In 1901, Sultan Hashim's financial situation deteriorated, leading him to borrow $10,000 from Brooke for household expenses. Amidst these difficulties, he arranged a lavish royal wedding for his grandson to strengthen political ties.[7] However, the Sultan firmly rejected Brooke and Hewett's proposal to cede the Belait and Tutong districts, concerned for the future of his dynasty.[8] As his dissatisfaction with British administration grew, Sultan Hashim expressed his willingness in 1903 to transfer Brunei to the Ottoman Empire due to what he saw as the oppression of Islam and the loss of territory.[9] Efforts to transfer Brunei to Sarawak ultimately failed after a smallpox epidemic in 1904 claimed the lives of the newlywed couple.[7]

McArthur's report and impact

[edit]The report produced by Malcolm McArthur after his 1904 expedition in Brunei was crucial in changing British perspectives toward the sultanate. Unlike previous assessments, McArthur's report offered a more balanced view, recognising Sultan Hashim's dignity and the challenges he faced. It highlighted the Sultan's feelings of abandonment and despair, providing a deeper understanding of his situation. McArthur's findings played a key role in shaping future interactions and governance in Brunei.[10]

Sultan Hashim agreed to McArthur's proposal to establish a British Residency system in Brunei.[11] The Sultan and his Wazirs signed the 1905–1906 Supplementary Treaty, which was formalised in early 1906 during Sir John Anderson's visit. Anderson praised McArthur for his reliable leadership, emphasizing its importance for Brunei's future. Sultan Hashim expressed his relief, thanking Anderson for his assurances regarding Brunei's Islamic status, reflecting the Sultan's efforts to protect Brunei through diplomatic agreements.[12]

The Wazirs saw a decrease in importance during British administration, primarily due to land reforms that impacted their means of survival and customary authority. After 1906, Sultan Hashim's standing as the head of state became more symbolic, while actual authority shifted significantly.[13] The establishment of the British Residency marked a new era, where the British Resident took on the role of governance.[14] Sultan Hashim faced ongoing challenges that resulted in the loss of important regions and severe poverty, affecting both the palace and the general public.[15]

Symbolic authority and real power

[edit]

Except in questions of religion and custom, Sultan Muhammad Jamalul Alam II's executive powers were passed to the British Resident with the implementation of the British Residency system.[16] Under his rule, he promoted Chinese settlement for their economic talents[17] and oversaw the adoption of syariah law in Brunei with the 1913 Marriage and Divorce Act and the 1912 Mohammedan Laws Enactment, which superseded the Kanun Brunei.[18][19]

During his reign, Brunei participated in the Malay and Borneo Cultural Festival in 1922, when he became the first Sultan to visit Singapore, escorted by traditional musicians.[20] Additionally, in 1909, he became the first Sultan to have his palace moved from Kampong Ayer to land.[21][22] The first crude oil find in Brunei was discovered in the same year, although significant oil strikes did not occur until 1927.[23] The Sultan also welcomed the Prince of Wales on 18 May 1922, showcasing the Sultanate's regal traditions.[24]

After his father's death, Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin assumed the throne and was marked by a more cautious attitude than his predecessor.[25] He often relied on international consultants over local leaders, like Gerard MacBryan, indicative of his ongoing reliance on outside influence.[26] To show his dissatisfaction with Brunei's structure, he often skipped State Council sessions between 1931 and 1950. He selected a competent personal assistant to help him navigate governance. Even though he became the first Sultan to attain complete sovereignty in 1931 at the age of 18, he later went to England to improve his language skills.[27]

Despite worries over the distribution of income from oil exports, Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin worked to strengthen financial rules for Brunei's residents. He was well-known for his hospitality to visitors, particularly high-ranking officials.[28] He attempted to build links throughout his rule, including a notable effort to wed the daughter of the Sultan of Selangor, which strengthened the bonds between the two royal houses.[29] However, by the late 1930s, his relationship with the British worsened, reflecting greater issues in Brunei's political environment and governance under colonial rule.[30]

In order to foster local governance, Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin pushed for the recruitment of 25 Bruneians to higher posts in the Brunei Administrative Service (BAS). This resulted in their appointment to the government bureaucracy in 1941. In an effort to further Islamic education, he founded a private Arabic school in 1940. It was forced to close in 1942 due to Japanese occupation.[31] Sultan backed the creation of regional defence units, such as the Brunei Volunteer Force, to help the British repel a Japanese invasion as tensions with Japan increased. But as the occupation progressed, his position became mostly symbolic, with the Japanese province governor holding actual authority. In spite of this, he was able to retake several areas that Brunei had previously lost, indicating a long-standing intention to take back control of these regions.[32]

The Sultan had little real influence during the occupation, but his status was preserved so the Japanese could win over the locals.[33] He was given decorations and a salary upon the country's surrender to the Japanese Army during World War II in December 1941, although his main role was that of ceremonial commander. Locals began to oppose the Japanese administration more and more, especially as food shortages got severe. Local authorities concealed the Sultan in order to shield him and his family from the increasing violence.[34] He was greeted as a hero upon his return when Australian forces liberated Brunei in June 1945, but he stayed under military rule until civilian governance was reinstated in July 1946.[35] As the British attempted to establish greater control over the area, the Sultan struggled to reclaim total authority in the post-war era due to persistent conflicts over administrative oversight and governance with the British Military Administration.[36]

Post-war Brunei

[edit]

Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin was portrayed by British envoy Malcolm MacDonald in July 1946 as a weak and indulgent king who was driven by excess and a lack of dedication to his royal duties.[37] In Brunei Town, a welcome arch was built during MacDonald's visit, bearing the words "Restorer of Peace and Justice" beneath the Union Jack, emphasising the rights of the Sultan and his subjects. The Sultan backed local emotions despite British instructions to change the words on the arch, a reflection of his complex relationship with colonial authority.[38]

Because MacDonald's proposal to maintain Brunei's independence from Sarawak and North Borneo was supported by the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Sultan was able to consolidate his control following World War II.[36] Sultan said that Brunei ought to have profited from any changes in territory, and he was unhappy with the British Crown's handling of Sarawak. As a demonstration of his support for the political movement, Brunei developed its national song, "Allah Peliharakan Sultan," and adopted the Barisan Pemuda's (BARIP) flag.[38] In an effort to improve relations, Resident Eric Pretty was reappointed in August 1948 as tensions between the Sultan and British authorities increased. He recommended that the Sultan write to the Secretary of State, highlighting Brunei's challenges and proposing the building of a new palace in place of the one that had been destroyed during the war.[39]

In 1950, Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin became increasingly political, frustrated by the British government's refusal to return his palace despite higher oil revenues. He sought to renegotiate Brunei's constitutional relationship with the Britain and pushed for increased oil royalties from British Malayan Petroleum. Planning a trip to London with his advisor MacBryan, the Sultan also expressed dissatisfaction with Brunei's oilfield concessions and Sarawak's cession. As Political Secretary, MacBryan advocated for including Muslims from northern Borneo and the southern Philippines in Brunei's post-war administration, a move that raised concerns for the British Colonial Office regarding its potential impact on Brunei's oil output and sovereignty. The Sultan's initiatives aimed to address economic challenges and enhance Brunei's standing in negotiations with Britain.[40]

After ascending to the throne, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III became the leader of the Islamic faith in Brunei, with a primary goal of improving the educational system.[41] In 1950, Brunei began sending students to the Al-Juned Arabic School in Singapore, and by 1963, the first Bruneian graduated from Al-Azhar University in Egypt, marking a significant advancement in regional Islamic education. The Sultan's administration allocated B$10.65 million to education in 1954, which funded the construction of 30 schools and the provision of free meals for students.[42] To accommodate the growing student population, notable secondary schools like Sultan Muhammad Jamalul Alam Secondary School and Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien College were built.[43] Additionally, the Department of Religious Affairs was established in 1954 to oversee Brunei's Islamic constitutional matters, leading to the opening of seven religious schools by 1956 and greatly enhancing Islamic education in the country.[42]

Brunei's oil sector grew rapidly beginning in 1950, with the country's first oil platform built in Seria in 1952. A $14 million gas pipeline was installed in 1955, and by 1956, the Seria field was producing 114,700 barrels of oil per day.[43] Since its founding in 1957, the Brunei Shell Petroleum firm has produced a substantial amount of crude oil and natural gasoline, totaling 705,000 tons and 39.5 million tons, respectively.[43] The 1st National Development Plan, initiated in 1953, prioritised public health and infrastructure,[44] with a B$100 million budget allocated for building Muara Port and developing transportation, telecommunication, energy, and water supply. This initiative also significantly reduced the number of malaria cases while improving public health through the provision of clean water and enhanced sanitation.[43][45] By 1958, B$4 million had been spent on education, and Brunei Airport was renovated in 1954, which greatly increased communication and transit.[43]

Constitution and independence

[edit]In early 1959, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III led a delegation to London to finalise Brunei's Constitution after the Merdeka Talks. Between 23 March and 6 April 1959, negotiations with British officials addressed key constitutional issues, including council meetings, elections, and the role of the Menteri Besar. An agreement was reached on 6 April 1959, leading to the phased implementation of the Constitution.[46] On 29 September 1959, the Sultan signed and proclaimed Brunei's first written Constitution,[47] which ended British control dating back to the 1888 and 1905–06 treaties and restored Brunei's sovereignty over its internal affairs.[48]

Politics

[edit]

Between 1888 and 1959, Brunei's political landscape was shaped by its relationship with the British Empire. In 1888, Brunei became a British protectorate through the Treaty of Protection, which gave Britain control over Brunei’s foreign affairs while allowing the Sultan to retain internal authority.[4] This period saw further erosion of Brunei’s sovereignty, particularly with the annexation of the Limbang district by Sarawak in 1890, despite Brunei's protests.[4] The British Residency system was formally introduced in 1906,[12] effectively transferring executive power from the Sultan to a British Resident,[13] except in matters of religion and local customs.[13] Oil was discovered in 1922,[23] dramatically increasing Brunei's strategic and economic importance.[43] However, during the reign of Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin, British Residents continued to hold substantial control, leading to tensions over governance and the distribution of wealth from oil.[40] The turning point came under Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III, who pushed for constitutional reforms.[49] In 1959, Brunei adopted its first written constitution, which restored much of its internal sovereignty while Britain retained control over defence and foreign affairs.[48]

The State Council of Brunei, established by the 1905–1906 Supplementary Treaty, serves as the principal advisory body to the Sultan, providing counsel on matters of governance and policy.[50] Its structure comprises various appointed members, including the British Resident, who acts as the chair, the Sultan and a mix of local dignitaries and officials, such as the Menteri Besar, cabinet ministers, and other representatives from the community.[51] The council played a key role in preserving the British government's quasi-colonial rule over Brunei's British citizens.[52] Sir Frank Swettenham described the council as a "great safety valve" that provided the enraged Malay nobilities and aristocrats with a forum for discussion apart from the customary meetings with the Sultan and his personal counsellors.[52]

BARIP was an early left-wing political party formed in Brunei in the late 1946.[53] Founded by Salleh Masri, Pengiran Muhammad Yusuf, and Jamil Al-Sufri,[54] BARIP aimed to unite Bruneian Malays and achieve independence for Brunei, inspired by nationalist movements across Southeast Asia.[55] The party adopted emblems like its Hidup Melayu motto and the Sang Saka Merah Putih flag, reflecting its support for the Indonesian National Revolution and symbolising the struggle against colonialism.[56][57] Although its existence was short-lived, BARIP played a vital role in promoting Malay nationalism and advocating for social issues,[55] including increased educational and employment opportunities for Bruneian Malays at the expense of Chinese people.[41] The Partai Rakyat Brunei, on the other hand, was a left-wing political party that was founded in 1956 with the intention of securing Brunei's complete independence from the United Kingdom. The party's goals were dashed in 1958 when the British suggested a gradual democratic transition of their own that would become the North Borneo Federation.[58]

Military

[edit]

Brunei's military was characterised by its dependence on British protection due to the kingdom's inherent limitations and the sultans' helplessness, as evidenced by the 1888 Treaty of Protection signed with Britain to preserve Brunei's geographical sovereignty, which was compromised when Brooke took control of the Limbang District in 1890, and a significant turning point occurred in 1906 when Sultan Hashim signed a Supplementary Treaty. The British did not deploy troops in Brunei at this time, therefore the sultans had no responsibility for maintaining state security. Instead, they offered military support. When the British departed during the Japanese occupation in 1941, Brunei's weakness was exposed. This showed the monarchy lacked fortifications and aided in its subsequent attempts to develop its own military capabilities.[59]

Brunei was to gain from this approach as Britain prepared to sever its colonial connections with Malaya and northern Borneo following the Pacific War. After being enthroned in May 1951, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien III started deliberations to draft Brunei's first written constitution, which included the notion of creating a military regiment. The Brunei Malay Constitutional Advisory Committee, also known as Tujuh Serangkai, advocated for the formation of the Brunei Regiment, a Malay-led army to uphold state security and protect the reputation of the Sultan's government without depending on outside military forces, unless absolutely required and approved by the State Council and District Councils.[60]

The Sultan agreed with the Tujuh Serangkai's suggestion to create Brunei's own regiment in order to boost the country's prestige, provide palace guards, salute, and assist local law enforcement with internal security responsibilities. The notion of creating a Malay regiment was not new; the first was formed during British Ceylon in 1798, and the second was formed in British Malaya in 1933. Brunei was the third country to create a Malay regiment. Furthermore, Brunei was part of the British Empire throughout World War II. In 1939, Malays, Ibans, and Chinese from the area formed the Volunteer Force, which helped destroy oil wells in preparation for the Japanese invasion while safeguarding important resources including rice stocks and oil fields. Concerns over the expanding Chinese population and the possible effect of the insurgency led by the Communist Party of Malaya in surrounding nations led to the establishment of a crude Special Branch in Brunei following the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949. Apart from that, military worries during this era led to the stationing of a Sarawak Field Force in Brunei from 1954 to 1961, which was mostly made up of Ibans and numbered around 300.[61]

Administration

[edit]The introduction of the British Residency system in 1906 brought a new administrative structure, with British officials advising the Sultan and overseeing key departments, leading to a centralisation of governance in Brunei Town, where Malay district officers reported to the British Resident across four districts. In 1908, the administrative districts of Brunei and Limau Manis were merged,[62] and although Brunei–Muara became the focal point for development efforts, attention shifted to other districts with the rise of the oil industry after 1932.[63] The present-day Brunei–Muara District was officially formed in 1938 through the merger of the Brunei, Limau Manis, and Muara administrative districts.[62] By 1947, Brunei's territory had contracted to approximately 2,226 square miles, with a population of around 40,670, primarily comprising the of Belait, Tutong, Temburong, and Brunei–Muara districts.[63]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Wright 1988, p. 230.

- ^ McArthur 1987.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2000, p. 323–324.

- ^ a b c d Hussainmiya 2006, p. 14.

- ^ a b Hussainmiya 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2006, p. 16.

- ^ a b Hussainmiya 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Mohd Jamil Al-Sufri (Pehin Orang Kaya Amar Diraja Dato Seri Utama Haji Awang.) 2008.

- ^ Mohd Jamil Al-Sufri (Pehin Orang Kaya Amar Diraja Dato Seri Utama Haji Awang.) 2000, p. 36.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2006, p. 25–30.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2006, p. 37.

- ^ a b Hussainmiya 2006, p. 52–53.

- ^ a b c Hussainmiya 2006, p. 57.

- ^ "Brunei". CIA World Factbook. 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2006, p. 22.

- ^ Horton 1986, p. 353–374.

- ^ Thumboo 1996, p. 35.

- ^ "Brunei (Negara Brunei Darussalam)". Emory University. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ DDW Hj Tamit 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Great Britain Colonial Office 1965, p. 226.

- ^ Indonesia, Malaysia & Singapore Handbook. New York: Trade & Trade & Travel Publications. 1996. p. 569. ISBN 978-0-8442-8886-4.

- ^ "Sultan-Sultan Brunei". Brunei History Centre (in Malay). Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ a b World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia. Marshall Cavendish. 2007. p. 1199. ISBN 978-0-7614-7642-9.

- ^ May 1998, p. 195.

- ^ Saunders 1994, p. 114.

- ^ Hussainmiya 1995, p. 74.

- ^ Reece 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Reece 2009, p. 86.

- ^ Muhammad Melayong 2009, p. 64.

- ^ Reece 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Reece 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Abdul Majid 2007, p. 12-13.

- ^ Saunders 2003, p. 129.

- ^ Zullkiflee 2019, p. 250.

- ^ Reece 2009, p. 87.

- ^ a b Reece 2009, p. 89.

- ^ Reece 2009, p. 106.

- ^ a b Hussainmiya 2003, p. 291.

- ^ Mohamed 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b Reece 2009, p. 90–98.

- ^ a b Ooi & King 2022.

- ^ a b Ahad 2015, p. 6–8.

- ^ a b c d e f Dayangku Herney Zuraidh binti Pengiran Haji Rosley 2007.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 129.

- ^ History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 96.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2019, p. 213.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2019, p. 214.

- ^ a b Siti Nor Anis Nadiah Haji Mohamad & Mariam Abdul Rahman 2021, p. 41–42.

- ^ Ahad 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Great Britain Colonial Office 1948, p. 78.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2000, p. 324.

- ^ a b Hussainmiya 2000, p. 321.

- ^ Shimizu, Bremen & Hakubutsukan 2003, p. 288.

- ^ Sidhu 2009, p. 154.

- ^ a b Prasetyo 2011, p. 29.

- ^ Welsh, Somiah & Loh 2021, p. 307.

- ^ Ahmad (Haji.) 2003, p. 24 and 26.

- ^ Awang Mohamad Yusop Damit 1995, p. 13–14.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2012, p. 6–7.

- ^ Hussainmiya 2012, p. 7–8.

- ^ a b Jabatan Muzium-Muzium Brunei 2004, p. 1.

- ^ a b Great Britain Colonial Office 1949, p. 100.

Sources

- Hussainmiya, B. A. (2019). The Making of Brunei's 1959 Constitution. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- Hussainmiya, B. A. (1 January 2012). "Royal Brunei Armed Forces 50th anniversary commemorative history". RBAF 50th Golden Anniversary Commemorative Book. South Eastern University of Sri Lanka.

- Hussainmiya, B. A. (2006). Brunei: Revival of 1906: A Popular History. Brunei Press. ISBN 978-99917-32-15-2.

- Hussainmiya, B. A. (26 December 2003). Resuscitating nationalism: Brunei under the Japanese Military Administration (1941-1945).

- Hussainmiya, B. A. (September 2000). ""Manufacturing Consensus": The Role of the State Council in Brunei Darussalam". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 31 (2). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- Hussainmiya, B. A. (1995). Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain, The Making of Brunei Darssalam. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

- Mohd Jamil Al-Sufri (Pehin Orang Kaya Amar Diraja Dato Seri Utama Haji Awang.) (2000). History of Brunei in Brief. Brunei History Centre, Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports. ISBN 978-99917-34-11-8.

- Mohd Jamil Al-Sufri (Pehin Orang Kaya Amar Diraja Dato Seri Utama Haji Awang.) (2008). Melayu Islam Beraja: hakikat dan hasrat (in Malay). Jabatan Pusat Sejarah, Kementerian Kebudayaan, Belia dan Sukan, Negara Brunei Darussalam. ISBN 978-99917-34-63-7.

- Thumboo, Edwin (1996). Cultures in ASEAN and the 21st Century. Unipress Corporation. ISBN 978-981-00-8174-4.

- Ooi, Keat Gin; King, Victor T. (29 July 2022). Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Brunei. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-56864-6.

- Horton, A. V. M. (1986). "British Administration in Brunei 1906-1959". Modern Asian Studies. 20 (2): 353–374. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00000871. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 312580. S2CID 144185859.

- Zullkiflee, Nurul Amalina (2019). Strategi Awang Haji Kassim dalam Usaha Menyelamatkan Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin: Satu Kajian Awal (PDF). Universiti Islam Sultan Sharif Ali.

- Saunders, Graham (2003). A History of Brunei (2nd ed.). Abingdon: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 9781138863453.

- Saunders, Graham E. (2002). A History of Brunei. Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1698-X.

- Saunders, Graham (1994). A History of Brunei (1st ed.). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9789676530493.

- Reece, Bob (2009). ""The Little Sultan": Ahmad Tajuddin II of Brunei, Gerard MacBryan, and. Malcolm Macdonald" (PDF). Borneo Research Bulletin. 40. Borneo Research Council. ISSN 0006-7806.

- Muhammad Melayong, Dr Muhammad Hadi (2009). Memoir seorang negarawan (in Malay). Bandar Seri Begawan: Brunei History Centre. ISBN 978-99917-34-69-9.

- Ahad, Nazirul Mubin (2015). "EFFORTS OF SULTAN HAJI OMAR ALI SAIFUDDIEN III IN PRESERVING ISLAMIC DOCTRINE OF AHLUS SUNNAH WAL JAMĀ'AH". Konferensi Antarabangsa Islam Borneo VIII. UNISSA. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- Shimizu, Akitoshi; Bremen, Jan van; Hakubutsukan, Kokuritsu Minzokugaku (2003). Wartime Japanese Anthropology in Asia and the Pacific. National Museum of Ethnology. ISBN 978-4-901906-21-0.

- Sidhu, Jatswan S. (22 December 2009). Historical Dictionary of Brunei Darussalam. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7078-9.

- Prasetyo (13 July 2011). Pergerakan Pemuda Di Brunei Darussalam (1946–1962) [Youth Movement In Brunei Darussalam (1946–1962)] (in Indonesian). Indonesia: Universitas Indonesia.

- Welsh, Bridget; Somiah, Vilashini; Loh, Benjamin Y. H. (3 May 2021). Sabah from the Ground: The 2020 Elections and the Politics of Survival. Strategic Information & Research Devt Centre/ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. ISBN 978-981-4951-69-2.

- Siti Nor Anis Nadiah Haji Mohamad; Mariam Abdul Rahman (15 November 2021). "Penggubalan Perlembagaan Negeri Brunei 1959: Satu Sorotan Sejarah" [Drafting of The Brunei Constitutions of 1959: A Historical Review]. The Sultan Alauddin Sulaiman Shah Journal. 8 (2). Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- Dayangku Herney Zuraidh binti Pengiran Haji Rosley (2007). "Pemerintahan Sultan Omar 'Ali Saifuddien III (1950-1967)" (PDF). www.history-centre.gov.bn (in Malay). Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- Abdul Majid, Harun (2007). Rebellion in Brunei: the 1962 revolt, imperialism, confrontation and oil. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781435615892.

- DDW Hj Tamit, Datin Dr. Hajah Saadiah (March 2006). "PENTADBIRAN UNDANG-UNDANG ISLAM DI NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM PADA ZAMAN BRITISH" (PDF). Akedemi Pengajian Brunei, Universiti Brunei Darussalam (in Malay). Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- McArthur, Malcolm Stewart Hannibal (1987). Report on Brunei in 1904. Ohio University Center for International Studies, Center for Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-0-89680-135-6.

- Great Britain Colonial Office (1965). Brunei. H.M. Stationery Office.

- Great Britain Colonial Office (1949). The Colonial Office List. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 100.

- Great Britain Colonial Office (1948). The Colonial Office List, Comprising Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the Colonial Empire, List of Officers Serving in the Colonies, Etc. H.M. Stationery Office.

- May, Gary (1 November 1998). Hard Oiler!: The Story of Canadians' Quest for Oil at Home and Abroad. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-4597-1312-3.

- Mohamed, Muhaimin (2002). Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin 1924–1940: Hubungan Raja dengan Penasihat (in Malay). Bandar Seri Begawan: Brunei History Centre. ISBN 99917-34-79-1.

- History for Brunei Darussalam: Sharing our Past. Curriculum Development Department, Ministry of Education. 2009. ISBN 978-99917-2-372-3.

- Ahmad (Haji.), Zaini Haji (2003). Brunei merdeka: sejarah dan budaya politik (in Malay). De'Imas Printing. ISBN 978-99917-34-01-9.

- Awang Mohamad Yusop Damit (1995). Brunei Darussalam 1944-1962: Constitutional and Political Development in a Malay-Muslim Sultanate. University of London.

- Jabatan Muzium-Muzium Brunei (2004). Sungai Limau Manis: Tapak Arkeologi Abad Ke-10 - 13 Masihi (in Malay). Jabatan Muzium-Muzium Brunei. ISBN 9991730184. OCLC 61123390.

- Wright, Leigh R. (1 July 1988). The Origins of British Borneo. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-213-6.

*

*

Category:20th century in Malaysia

Category:20th century in Singapore

Category:1819 establishments in Asia

Category:1819 establishments in the British Empire

Category:1957 disestablishments in Asia

Category:1957 disestablishments in the British Empire

Category:Former countries in Malaysian history

Category:Malaya

Category:States and territories disestablished in 1957

Category:States and territories established in 1819

Malaya

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).